Amino acid surfactants (AAS) are a class of surfactants formed by combining a hydrophobic group with one or more amino acids. The amino acids can be synthetic or derived from protein hydrolysates or similar renewable resources. This article covers details of most available synthesis routes for AAS, as well as the impact of different routes on the physicochemical properties of the final products, including solubility, dispersion stability, toxicity, and biodegradability. As a class of surfactants with growing demand, the diversity arising from the structural variability of AAS provides numerous commercial opportunities.

Given that surfactants are widely used in detergents, emulsifiers, corrosion inhibitors, enhanced oil recovery, and pharmaceuticals, researchers’ attention to surfactants has never waned.

Surfactants are among the most representative chemical products consumed in large quantities globally every day, and they have adversely affected aquatic environments. Studies show that the widespread use of traditional surfactants can have detrimental effects on the environment.

Today, for consumers, non-toxicity, biodegradability, and biocompatibility are almost as important as the functionality and performance of surfactants.

Biosurfactants are green, sustainable surfactants naturally synthesized by microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, and yeast, or secreted extracellularly. Therefore, biosurfactants can also be prepared by molecular design to mimic natural amphiphilic structures (such as phospholipids, alkyl glycosides, and acyl amino acids).

Amino acid surfactants (AAS) are a typical type of such surfactants, usually produced from animal or agriculturally derived raw materials. In the past 20 years, AAS as novel surfactants have attracted great interest from scientists, not only because AAS can be synthesized using renewable resources, but also because AAS are easily degradable with harmless byproducts, making them safer for the environment.

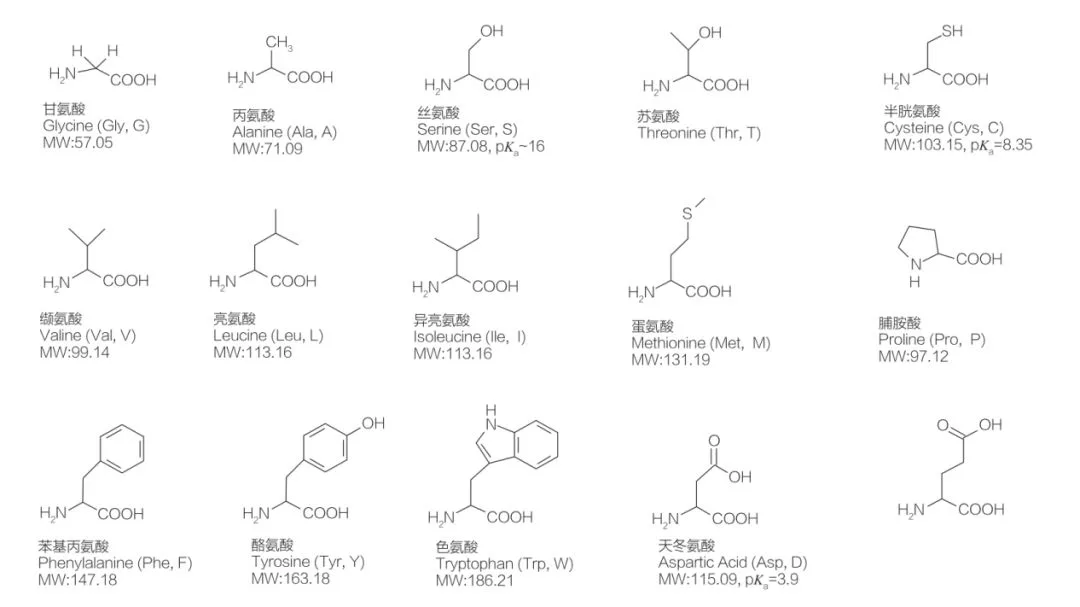

AAS can be defined as a class of surfactants composed of amino acids containing amino acid groups (HO2C-CHR-NH2) or amino acid residues (HO2C-CHR-NH-). The two functional regions of amino acids allow for the derivation of a wide variety of surfactants. There are 20 known standard proteinogenic amino acids in nature, responsible for all physiological reactions in growth and life activities. They differ from each other only based on the different residue R (Figure 1, where pKa is the negative logarithm of the acid dissociation constant of the solution). Some are non-polar and hydrophobic, some are polar and hydrophilic, some are basic, and some are acidic.

Since amino acids are renewable compounds, surfactants synthesized from amino acids have great potential to become sustainable and environmentally friendly substances. Their simple and natural structure, low toxicity, and rapid biodegradability often make them superior to traditional surfactants. Using renewable raw materials (such as amino acids and vegetable oils), AAS can be produced through different biotechnological and chemical routes.

In the early 20th century, amino acids were first discovered as substrates for synthesizing surfactants. AAS are mainly used as preservatives in pharmaceutical and cosmetic formulations. Additionally, AAS have been found to possess biological activity against various pathogenic bacteria, tumors, and viruses. In 1988, the availability of low-cost AAS sparked interest in surface activity research. Today, with the development of biotechnology, some amino acids can be commercially synthesized on a large scale through yeast, indirectly proving that AAS production is more environmentally friendly.

History

As early as the early 19th century, when naturally occurring amino acids were just discovered, their structures were predicted to be highly valuable—as raw materials for preparing amphiphiles. The first study on AAS synthesis was reported by Bondi in 1909.

In that study, N-acyl glycine and N-acyl alanine were introduced as hydrophilic groups for surfactants. Subsequent work involved synthesizing lipoamino acids using glycine and alanine. Hentrich et al. published a series of research results, including the first patent on using acyl sarcosinates and acyl aspartates as surfactants in household cleaning products (such as shampoos, detergents, and toothpastes). Subsequently, many researchers studied the synthesis and physicochemical properties of acyl amino acids. To date, there is a large body of literature on the synthesis, properties, industrial applications, and biodegradability of AAS.

Structural Characteristics

The non-polar hydrophobic fatty acid chains of AAS may differ in structure, chain length, and number. The structural diversity and high surface activity of AAS explain their wide compositional diversity and physicochemical and biological properties. The head group of AAS consists of amino acids or peptides. Differences in the head group determine the adsorption, aggregation, and biological activity of these surfactants. The functional groups in the head group determine the type of AAS, including cationic, anionic, non-ionic, and amphoteric. The combination of hydrophilic amino acids and hydrophobic long-chain parts forms an amphiphilic structure, giving the molecule high surface activity. Additionally, the presence of asymmetric carbon atoms in the molecule helps form chiral molecules.

Chemical Composition

All peptides and polypeptides are polymerization products of nearly 20 proteinogenic α-amino acids. All 20 α-amino acids contain a carboxylic acid functional group (—COOH) and an amino functional group (—NH2), both connected to the same tetrahedral α-carbon atom. Amino acids differ from each other in the different R groups attached to the α-carbon (except for glycine, where the R group is hydrogen). R groups may differ in structure, size, and charge (acidity, basicity). These differences also determine the solubility of amino acids in water.

Amino acids are chiral (except glycine), essentially because four different substituents are attached to the α-carbon, thus possessing optical activity. Amino acids have two possible configurations; they are non-superimposable mirror images of each other, although in fact, the number of L-stereoisomers is significantly higher. The R groups present in certain amino acids (phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan) are aryl, leading to maximum UV absorption at 280 nm. The acidic α-COOH and basic α-NH2 in amino acids can ionize, and both stereoisomers can build the ionization equilibrium as shown below:

R-COOH ↔ R-COO– + H+

R-NH3+ ↔ R-NH2 + H+

As shown in the above ionization equilibrium, amino acids contain at least two weakly acidic groups; however, the acidity of the carboxyl group is much stronger than that of the protonated amino group. At pH 7.4, the carboxyl group is deprotonated, while the amino group is protonated. Amino acids with non-ionizable R groups are electrically neutral at this pH and form zwitterions.

Classification

AAS can be classified according to four criteria, introduced below.

Based on Origin

Based on origin, AAS can be divided into the following two categories.

Natural Class

Some naturally occurring compounds containing amino acids also have the ability to reduce surface/interfacial tension, some even surpassing the efficacy of glycolipids. These AAS are also known as lipopeptides. Lipopeptides are low-molecular-weight compounds, usually produced by Bacillus species. This class of AAS is further divided into three subclasses: surfactin, iturin, and fengycin.

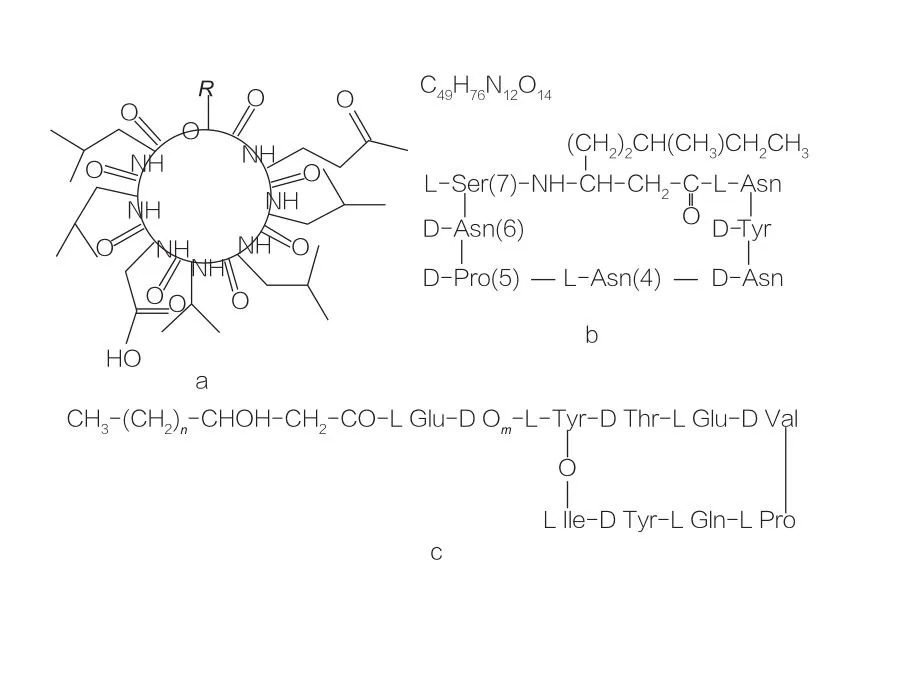

The surfactin family encompasses variants of heptapeptides of various substances, as shown in Figure 2a. In this type of surfactant, a C12-C16 unsaturated β-hydroxy fatty acid chain is linked to the peptide. Surfactin is a macrolactone where the β-hydroxy fatty acid and the C-terminus of the peptide form a ring through catalysis.

In the iturin subclass, there are mainly six variants: iturin A and C, mycosubtilin, and bacillomycin D, F, and L. In all cases, the heptapeptide is linked to a C14-C17 chain of β-amino fatty acids (the chain can be diverse). In iturin, the amino at the β-position forms an amide bond with the C-terminus to constitute the structure of a macrolactam.

The fengycin subclass includes fengycin A and B, also known as plipastatin when Tyr9 is D-configured. The decapeptide is linked to a C14-C18 saturated or unsaturated β-hydroxy fatty acid chain. Structurally, fengycin is also a macrolactone, containing a Tyr side chain at position 3 of the peptide sequence and forming an ester bond with the C-terminal residue, thus forming an internal cyclic structure (as in many Pseudomonas lipopeptides).

Synthetic Class

AAS can also be synthesized using any acidic, basic, or neutral amino acid. Common amino acids used for synthesizing AAS include glutamic acid, serine, proline, aspartic acid, glycine, arginine, alanine, leucine, and protein hydrolysates. Surfactants in this subclass can be prepared by chemical, enzymatic, or chemoenzymatic methods; however, chemical synthesis is more economically feasible for producing AAS. Common examples include N-lauroyl-L-glutamic acid and N-palmitoyl-L-glutamic acid.

Based on Aliphatic Chain Substituents

Based on fatty chain substituents, amino acid-based surfactants can be divided into two types.

Based on Substituent Position

- N-Substituted AAS

- In N-substituted compounds, an amino group is replaced by a lipophilic group or carboxyl, leading to loss of basicity. The simplest example of N-substituted AAS is N-acyl amino acids, which are essentially anionic surfactants. N-substituted AAS have an amide bond connecting the hydrophobic and hydrophilic parts. The amide bond has the ability to form hydrogen bonds, facilitating the degradation of this surfactant in acidic environments, making it biodegradable.

- C-Substituted AAS

- In C-substituted compounds, substitution occurs on the carboxyl group (via an amide or ester bond). Typical C-substituted compounds (such as esters or amides) are essentially cationic surfactants.

- N- and C-Substituted AAS

- In this type of surfactant, both the amino and carboxyl groups are part of the hydrophilic portion. This type is essentially amphoteric surfactants.

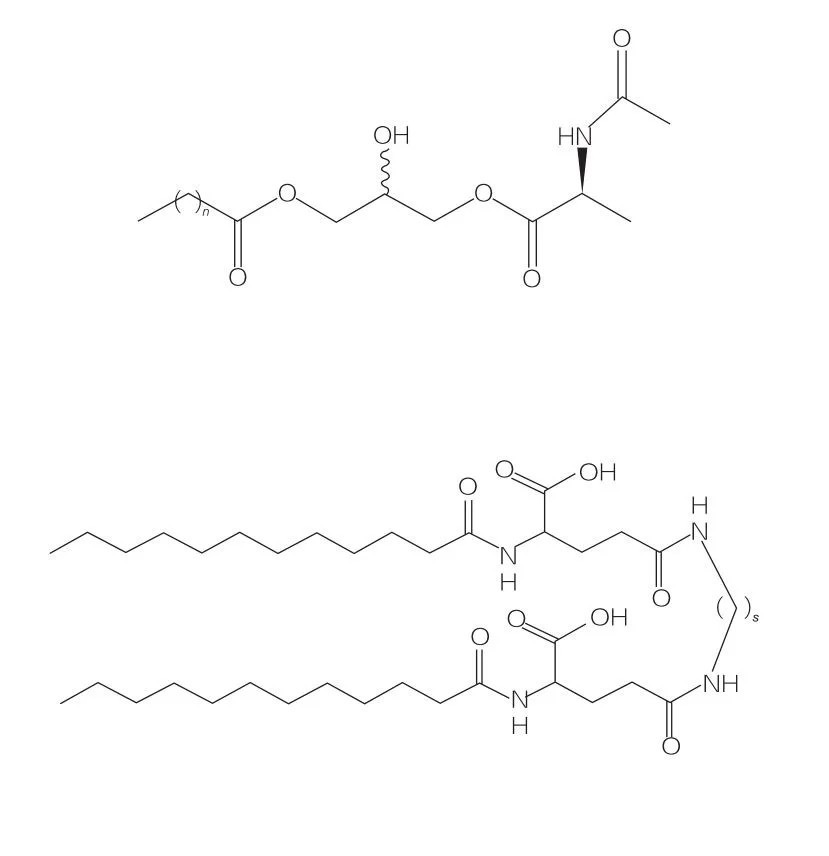

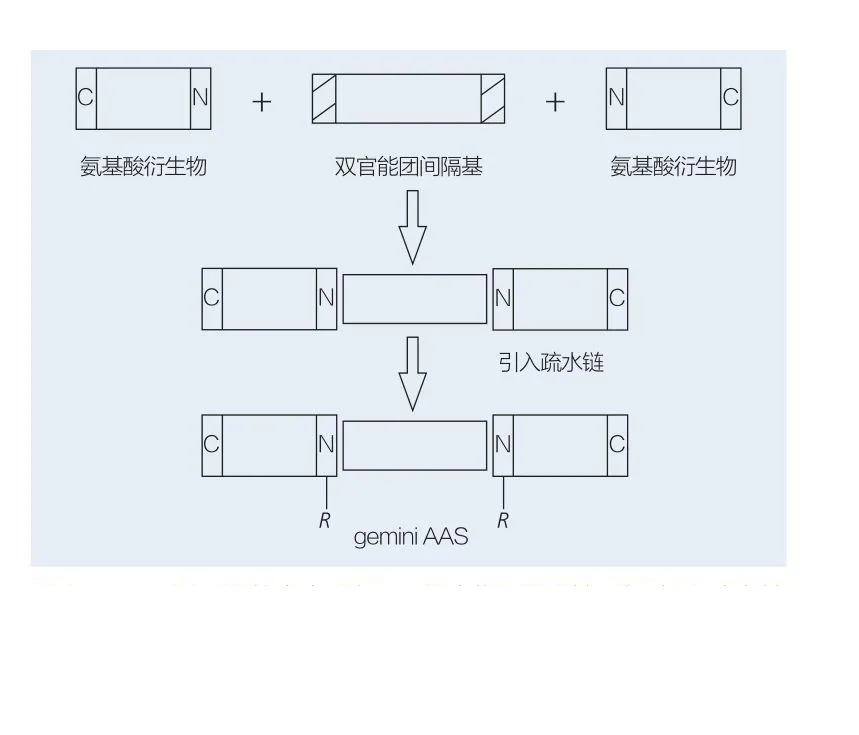

Based on the Number of Hydrophobic Tails

Based on the number of head groups and hydrophobic tails, AAS can be divided into four groups: linear AAS, Gemini (dimeric) AAS, glycerolipid AAS, and bolaform AAS. Linear surfactants are surfactants composed of amino acids with only one hydrophobic tail (Figure 3). Gemini AAS have two amino acid polar head groups and two hydrophobic tails per molecule (Figure 4). In this structure, two linear AAS are linked together by a spacer, hence also called dimers. In glycerolipid AAS, two hydrophobic tails are connected to the same amino acid head group (Figure 5). These surfactants can be seen as analogs of monoglycerides, diglycerides, and phospholipids. Bola AAS have two amino acid head groups linked by one hydrophobic tail (Figure 6).

Based on Head Group Type

Cationic AAS

This type of surfactant has a positively charged head group. The earliest cationic AAS is cocoyl arginine ethyl ester, a pyrrolidone carboxylate. This surfactant has unique and diverse properties, making it useful in disinfectants, antibacterials, antistatics, hair conditioners, and it is mild on eyes and skin, as well as biodegradable. Singare and Mhatre synthesized cationic AAS based on arginine and evaluated their physicochemical properties. In this study, they claimed high yields using Schotten-Baumann reaction conditions. As the alkyl chain length increases and hydrophobicity enhances, the surface activity of the surfactant increases, and the critical micelle concentration (CMC) decreases. Another is quaternary acyl protein, usually used as a conditioner in hair care products.

Anionic AAS

In anionic surfactants, the polar head group of the surfactant carries a negative charge. Sarcosinate surfactants are a type of anionic AAS. Sarcosine (CH3—NH—CH2—COOH, N-methylglycine) is an amino acid commonly found in sea urchins and starfish, chemically related to glycine (NH2—CH2—COOH), a basic amino acid found in mammalian cells. Lauric acid, myristic acid, oleic acid, and their halides and esters are typically used to synthesize sarcosinate surfactants. Sarcosinates are inherently mild and are commonly used in mouthwashes, shampoos, spray shaving foams, sunscreens, skin cleansers, and other cosmetics.

Other commercial anionic AAS include Amisoft CS-22 and Amilite GCK-12, which are trade names for sodium N-cocoyl-L-glutamate and potassium N-cocoyl glycinate, respectively. Amilite is commonly used as a foaming agent, detergent, solubilizer, emulsifier, and dispersant, with many applications in cosmetics such as shampoos, bath soaps, body washes, toothpastes, facial cleansers, cleansing soaps, contact lens cleaners, and household surfactants [50]. Amisoft is used as a mild skin and hair cleanser, mainly in facial and body cleansing products, syndet bars, body care products, shampoos, and other skincare products.

Amphoteric (Zwitterionic) AAS

Amphoteric surfactants contain both acidic and basic sites, so they can change charge by altering pH. In basic media, they behave like anionic surfactants, in acidic environments like cationic surfactants, and in neutral media like amphoteric surfactants. Lauroyl lysine (LL) and alkoxy (2-hydroxypropyl) arginine are the only known amino acid-based amphoteric surfactants. LL is the condensation product of lysine and lauric acid. Due to the amphoteric structure of LL, it is insoluble in almost all types of solvents except for strongly basic or acidic ones. As an organic powder, LL has excellent adhesion to hydrophilic surfaces and low friction coefficient, giving this surfactant excellent lubricating ability. LL is widely used in skin creams and conditioners, also as a lubricant.

Non-Ionic AAS

Non-ionic surfactants are characterized by a polar head group without a formal charge. Al-Sabagh et al. prepared eight novel ethoxylated non-ionic surfactants using oil-soluble α-amino acids. In this process, L-phenylalanine (LEP) and L-leucine were first esterified with hexadecanol, then amidated with palmitic acid, yielding two amides and two esters of α-amino acids. The amides and esters were then condensed with ethylene oxide to prepare three phenylalanine derivatives with different numbers of polyoxyethylene units (40, 60, and 100). These non-ionic AAS were found to have good detergency and foaming properties.

Synthesis

Basic Synthesis Routes

In AAS, the hydrophobic group can be attached to the amine or carboxylic acid site, or connected through the side chain of the amino acid. Based on this, there are four basic synthesis routes available, as shown in Figure 7.

- Amphiphilic ester amines are generated through esterification, where the synthesis of the surfactant is typically achieved by refluxing fatty alcohols and amino acids in the presence of dehydrating agents and acidic catalysts. In some reactions, sulfuric acid serves both as catalyst and dehydrating agent.

- Activated amino acids react with alkylamines to form amide bonds, synthesizing amphiphilic amidoamines.

- Amido acids are synthesized by reacting the amino group of amino acids with fatty acids.

- Long-chain alkyl amino acids are synthesized by reacting the amino group with haloalkanes.

Advances in Synthesis and Production

Synthesis of Single-Chain Amino Acid/Peptide Surfactants

N-acyl or O-acyl amino acids or peptides can be synthesized through enzyme-catalyzed acylation of amino or hydroxyl groups with fatty acids. The earliest report on solvent-free lipase-catalyzed synthesis of amino acid amides or methyl ester derivatives used Candida antarctica, with yields ranging from 25% to 90% depending on the target amino acid. In some reactions, methyl ethyl ketone was also used as a solvent. Vonderhagen et al. also described N-acylation reactions of amino acids, protein hydrolysates, and/or their derivatives catalyzed by lipases and proteases, using mixtures of water and organic solvents (such as dimethylformamide/water) and methyl butyl ketone.

Early on, the main problem with enzymatic synthesis of AAS was low yields. According to Valivety et al., even using different lipases and incubating at 70°C for many days, the yield of N-myristoyl amino acid derivatives was only 2%~10%. Montet et al. encountered low yield issues with amino acids when synthesizing N-acyl lysine using fatty acids and vegetable oils. According to their report, the maximum yield was 19% under solvent-free conditions and using organic solvents. Valivety et al. faced the same issue when synthesizing N-Cbz-L-lysine or N-Cbz-lysine methyl ester derivatives.

In this study, they claimed that using N-protected serine as substrate and Novozyme 435 as catalyst in a molten solvent-free environment, the yield of 3-O-myristoyl-L-serine was 80%. Nagao and Kito studied the O-acylation reactions of L-serine, L-homoserine, L-threonine, and L-tyrosine (LET) using lipases (obtained from Candida cylindracea and Rhizopus delemar in aqueous buffer media), reporting low acylation yields for L-homoserine and L-serine, while L-threonine and LET showed no acylation.

Many researchers support using inexpensive and readily available substrates to synthesize cost-effective AAS. Soo et al. claimed that immobilized lipase (lipoenzyme) works best in preparing palm oil-based surfactants. They noted that although the reaction takes a long time (6 days), the product yield is better. Gerova et al. studied the synthesis and surface activity of chiral N-palmitoyl AAS mixtures (optical/racemic) based on methionine, proline, leucine, threonine, phenylalanine, and phenylglycine. Pang and Chu described the copolycondensation reaction in solution of amino acid-based monomers and dicarboxylic acid-based monomers, synthesizing a series of functional, biodegradable amino acid-based polyamide esters.

Cantacuzene and Guerreiro reported the esterification of Boc-Ala-OH and Boc-Asp-OH carboxylic acid groups with long-chain fatty alcohols and diols, using dichloromethane as solvent and Sepharose 4B as catalyst. In this study, Boc-Ala-OH reacted well with fatty alcohols up to 16 carbon atoms (51% yield), while for Boc-Asp-OH, 6 and 12 carbon atoms were better, with corresponding yields of 63% [64]. Clapes et al. reported yields of 58%~76% for N-arginine alkyl amide derivatives (purity 99.9%) in the presence of papain (from papaya latex), synthesized by forming amide bonds between Cbz-Arg-OMe and various long-chain alkylamines or ester bonds with fatty alcohols, with papain as catalyst.

Synthesis of Gemini Amino Acid/Peptide Surfactants

Amino acid-based gemini surfactants consist of two linear AAS molecules linked head-to-head by a spacer. There are two possible schemes for chemoenzymatic synthesis of gemini amino acid-based surfactants (Figures 8 and 9). In Figure 8, two amino acid derivatives react with a compound as spacer, then two hydrophobic groups are introduced. In Figure 9, two linear structures are directly connected by a bifunctional spacer.

Valivety et al. were the first to develop enzymatic synthesis of gemini lipoamino acids. Yoshimura et al. studied the synthesis, adsorption, and aggregation of amino acid-based gemini surfactants based on cystine and n-alkyl bromides, comparing them to corresponding monomeric surfactants. Faustino et al. described the synthesis of anionic urea-based monomeric AAS and their gemini counterparts based on L-cystine, D-cystine, DL-cystine, L-cysteine, L-methionine, and L-sulfalanine, characterizing them by conductivity, equilibrium surface tension, and steady-state fluorescence. The study showed that gemini have lower CMC values compared to monomers.

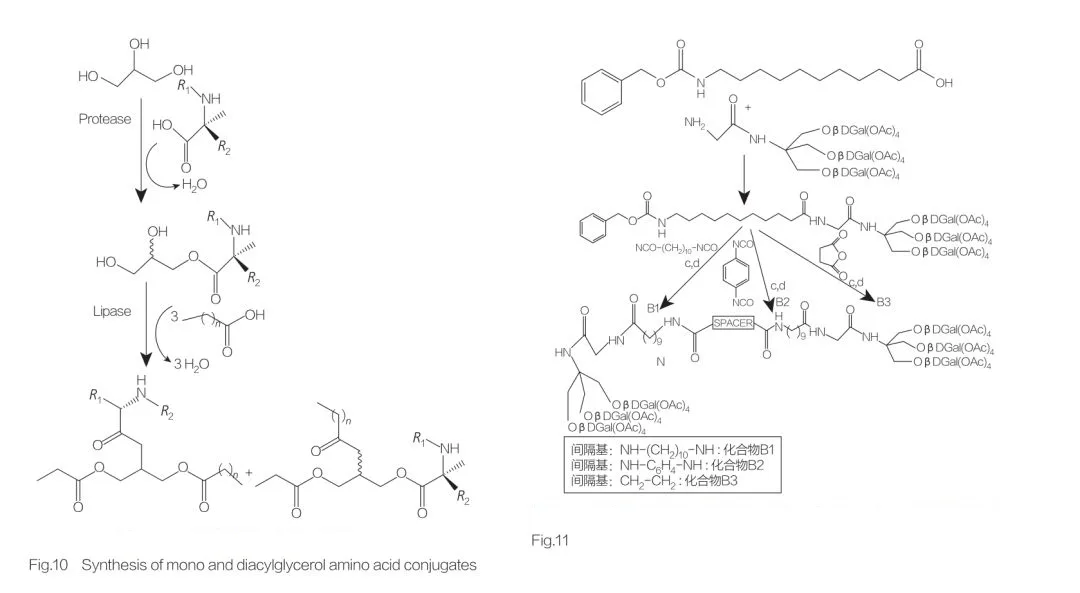

Synthesis of Glycerolipid Amino Acid/Peptide Surfactants

Glycerolipid amino acid/peptide surfactants are a new class of lipoamino acids, structural analogs of monoglycerides (or diglycerides) and phospholipids, with their structure being 1 or 2 fatty chains linked to 1 amino acid via ester bonds to a glycerol backbone. The synthesis of this type of surfactant first prepares the glycerol ester of the amino acid at elevated temperature and in the presence of an acidic catalyst (such as BF3). Enzymatic synthesis (using hydrolases, proteases, and lipases as catalysts) is also a good choice (Figure 10). The enzymatic synthesis of dilauroyl arginine glycerol conjugates using papain has been reported. The synthesis of diacyl glycerol lipid conjugates from acetyl arginine and evaluation of their physicochemical properties have also been reported.

Synthesis of Bola Amino Acid/Peptide Surfactants

Amino acid-based bola amphiphiles contain two amino acids connected to the same hydrophobic chain. Franceschi et al. described the synthesis of bola amphiphiles with two amino acids (D- or L-alanine or L-histidine) and one alkyl chain of varying length, studying their surface activity. They discussed the synthesis and aggregation of novel bola amphiphiles with amino acid parts (using uncommon β-amino acids or an alcohol) and C12-C20 spacers. The uncommon β-amino acids used can be sugar amino acids, an azidothymidine (AZT)-derived amino acid, a norbornene amino acid, and an AZT-derived amino alcohol (Figure 11). Polidori et al. described the synthesis of symmetric bola amphiphiles derived from tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris) (Figure 11).

Physicochemical Properties

It is well known that amino acid surfactants (AAS) have diverse properties and wide applications, with good suitability in many uses, such as good solubilization, emulsification, high efficiency, high surface activity, and good hard water resistance (calcium ion tolerance).

The properties of amino acid surfactants (such as surface tension, CMC, phase behavior, and Krafft temperature) have been extensively studied, concluding that the surface activity of AAS is superior to that of their corresponding traditional surfactants.

Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC)

Critical micelle concentration is one of the important parameters of surfactants, governing many surface properties such as solubilization, cytolysis, and interactions with biomembranes. Generally, increasing the hydrocarbon tail chain length (increasing hydrophobicity) leads to a decrease in the CMC of surfactant solutions, thereby increasing their surface activity. Compared to traditional surfactants, amino acid surfactants typically have lower CMC values.

Infante et al. synthesized three arginine-based AAS through different combinations of head groups and hydrophobic tails (mono-cationic amide, di-cationic amide, di-cationic amid ester) and studied their CMC and γCMC (surface tension at CMC), showing that as the hydrophobic tail length increases, CMC and γCMC decrease. In another study, Singare and Mhatre found that the CMC of N-α-acyl arginine surfactants decreases with increasing carbon atoms in the hydrophobic tail (see table below).

Table 1 Cmc and Surface Tension of N-α-Acyl Arginine Surfactants

| Property | N-α-Octanoyl-L-arginine Ethyl Ester (CAE) | N-α-Nonanoyl-L-arginine Ethyl Ester (NAE) | N-α-Lauroyl-L-arginine Ethyl Ester (LAE) | N-α-Myristoyl-L-arginine Ethyl Ester (MAE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cmc / (mg·L⁻¹) | >1500 | 820 ± 50 | 410 ± 10 | 350 ± 30 |

| γ / (mN·m⁻¹) | 27.0 ± 0.5 | 26.1 ± 0.5 | 25.5 ± 0.5 | 24.0 ± 0.5 |

Yoshimura et al. studied the CMC of cysteine-derived amino acid-based gemini surfactants, showing that as the carbon chain length in the hydrophobic chain increases from 10 to 12, CMC decreases. Further increasing to 14 leads to an increase in CMC, confirming that long-chain gemini surfactants have lower aggregation tendency.

Faustino et al. reported the formation of mixed micelles in aqueous solutions of cystine-based anionic gemini surfactants. Gemini surfactants were compared to corresponding traditional monomeric surfactants (C8 Cys). The CMC values of lipid-surfactant mixtures were reported to be lower than those of pure surfactants. The CMC of gemini surfactants and 1,2-diheptanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (a water-soluble, micelle-forming phospholipid) is in the millimolar range.

Shrestha and Aramaki studied the formation of viscoelastic worm-like micelles in aqueous solutions of mixed amino acid-based anionic-nonionic surfactants without added salt. In this study, N-dodecyl glutamic acid was found to have a higher Krafft temperature; however, after neutralization with basic amino acid L-lysine, it formed micelles, and the solution began to behave like a Newtonian fluid at 25°C.

Good Water Solubility

The good water solubility of AAS is due to the presence of an additional CO-NH bond. This makes AAS more biodegradable and environmentally friendly compared to corresponding traditional surfactants. N-acyl-L-glutamic acid has even better water solubility due to its two carboxyl groups. Cn(CA)2 also has good water solubility because there are two ionic arginine groups in one molecule, making adsorption and diffusion at the cell interface more effective, even at lower concentrations for effective bacteriostasis.

Krafft Temperature and Krafft Point

Krafft temperature can be understood as the special solubility behavior of surfactants, where the solubility of these surfactants sharply increases above a certain temperature. Ionic surfactants tend to form solid hydrates, which can precipitate from water. At a certain temperature (the so-called Krafft temperature), a sharp and discontinuous increase in surfactant solubility is usually observed. The Krafft point of ionic surfactants is the Krafft temperature at their CMC.

This solubility characteristic is commonly seen in ionic surfactants and can be explained as follows: below the Krafft temperature, the solubility of free surfactant monomers is limited until the Krafft point is reached, after which solubility gradually increases due to micelle formation. To ensure complete dissolution, it is necessary to prepare surfactant formulations above the Krafft point.

There have been many studies on the Krafft temperature of AAS, compared to traditional synthetic surfactants. Shrestha and Aramaki studied the Krafft temperature of arginine-based AAS, finding that their critical micelle concentration exhibits pre-micelle aggregation behavior above 2~5×10-6 mol·L-1, followed by normal micelle formation (at 3~6×10-4 mol·L-1). Ohta et al. synthesized six different types of N-hexadecanoyl AAS and discussed the relationship between their Krafft temperature and amino acid residues.

In the experiment, the Krafft temperature of N-hexadecanoyl AAS increases as the size of the amino acid residue decreases (except for phenylalanine), while the heat of dissolution (endothermic) increases as the amino acid residue size decreases (except for glycine and phenylalanine). It was concluded that in both alanine and phenylalanine systems, D-L interactions in solid N-hexadecanoyl AAS salts are stronger than L-L interactions.

Brito et al. used differential scanning calorimetry to determine the Krafft temperature of three series of novel amino acid-based surfactants, finding that changing trifluoroacetate ions to iodide ions leads to a significant increase in Krafft temperature (about 6°C), from 47°C to 53°C. The presence of cis double bonds and unsaturation in long-chain Ser-derivatives significantly lowers the Krafft temperature. N-dodecyl glutamic acid is reported to have a high Krafft temperature. However, after neutralization with basic amino acid L-lysine, micelles form in the solution, behaving like a Newtonian fluid at 25°C.

Surface Tension

The surface tension of surfactants is related to the chain length of the hydrophobic part. Zhang et al. measured the surface tension of sodium cocoyl glycinate using the Wilhelmy plate method at (25±0.2)°C, determining the surface tension at CMC as 33 mN·m-1, with CMC of 0.21 mmol·L-1. Yoshimura et al. measured the surface tension of 2Cn Cys amino acid-based surfactants [83]. Results showed that surface tension at CMC decreases with increasing chain length (until n = 8), while for n = 12 or longer chain surfactants, the trend is opposite.

The effect of CaCl2 on the surface tension of dicarboxylic amino acid surfactants has also been studied [84,85]. In these studies, CaCl2 was added to aqueous solutions of three dicarboxylic amino acid surfactants (C12 MalNa2, C12 AspNa2, C12 GluNa2). Comparing plateau values after CMC, surface tension decreases at very low CaCl2 concentrations. This is due to the influence of calcium ions on the arrangement of surfactants at the air-water interface. The surface tension of salts of N-dodecyl aminomalonic acid and N-dodecyl aspartic acid remains almost unchanged up to 10 mmol·L-1 CaCl2 concentration. Above 10 mmol·L-1, surface tension sharply increases due to the formation of surfactant calcium salt precipitates. For disodium N-dodecyl glutamate, moderate addition of CaCl2 leads to significant surface tension reduction, while further increasing CaCl2 concentration causes no significant change.

To determine the adsorption kinetics of gemini AAS at the air-water interface, dynamic surface tension was measured using the maximum bubble pressure method. Results showed no change in dynamic surface tension of 2C12 Cys for the longest test time. The decrease in dynamic surface tension depends only on concentration, hydrophobic tail length, and number of hydrophobic tails. Increasing surfactant concentration, decreasing chain length and number leads to faster decay. Results for higher concentrations of Cn Cys (n = 8~12) were very close to γCMC measured by Wilhelmy method.

In another study, dynamic surface tension of sodium dilauroyl cystinate (SDLC) and sodium didecanoyl cystinate was measured by Wilhelmy plate method, and equilibrium surface tension of their aqueous solutions by drop volume method. Further studies on disulfide bond reactions were done using other methods. Adding mercaptoethanol to 0.1 mmol·L-1 SDLC solution led to a rapid increase in surface tension from 34 mN·m-1 to 53 mN·m-1. Since NaClO can oxidize SDLC’s disulfide bond to sulfonic acid group, when NaClO (5 mmol·L-1) was added to 0.1 mmol·L-1 SDLC solution, no aggregates were observed. Transmission electron microscopy and dynamic light scattering results showed no aggregate formation in the solution. SDLC’s surface tension increased from 34 mN·m-1 to 60 mN·m-1 over 20 minutes.

Binary Surface Interactions

In the life sciences field, many groups have studied the vibrational properties of mixtures of cationic AAS (diacylglycerol arginine-based surfactants) and phospholipids at the air-water interface, concluding that this non-ideal characteristic causes the universality of electrostatic interactions.

Aggregation Properties

Dynamic light scattering is often used to measure the aggregation properties of amino acid-based monomeric and gemini surfactants at concentrations above CMC, yielding apparent hydrodynamic diameter DH (= 2RH). Compared to other surfactants, aggregates formed by Cn Cys and 2Cn Cys are relatively large with wide size distribution. Except for 2C12 Cys, other surfactants typically form aggregates of about 10 nm. The micelle size of gemini surfactants is significantly larger than that of their monomeric counterparts. Increasing hydrocarbon chain length also leads to larger micelle size. Ohta et al. described the aggregation properties of aqueous solutions of three different stereoisomers of N-dodecyl-phenyl-alanyl-phenyl-alanine tetramethylammonium, showing that diastereomers have the same critical aggregation concentration in aqueous solution. Iwahashi et al. studied the formation of chiral aggregates of optically active N-lauroyl-L-glutamic acid, N-lauroyl-L-valine, and their methyl esters in different solvents (such as tetrahydrofuran, acetonitrile, 1,4-dioxane, and 1,2-dichloroethane) using circular dichroism, NMR, and vapor pressure osmometry.

Interfacial Adsorption

The interfacial adsorption of amino acid surfactants and comparison with traditional counterparts is also a research direction. For example, studying the interfacial adsorption properties of dodecyl esters of aromatic amino acids obtained from LET and LEP. Results show that LET and LEP exhibit lower interfacial areas at gas-liquid and water/hexane interfaces, respectively.

Bordes et al. studied the solution behavior and adsorption at the air-water interface of three dicarboxylic amino acid surfactants: disodium salts of dodecyl glutamic acid, dodecyl aspartic acid, and aminomalonic acid (with 3, 2, 1 carbon atoms between the two carboxyl groups, respectively). According to the report, the CMC of dicarboxylic surfactants is 4~5 times higher than that of monocarboxylic dodecyl glycinate. This is attributed to hydrogen bonds formed by dicarboxylic surfactants through their amide groups with adjacent molecules.

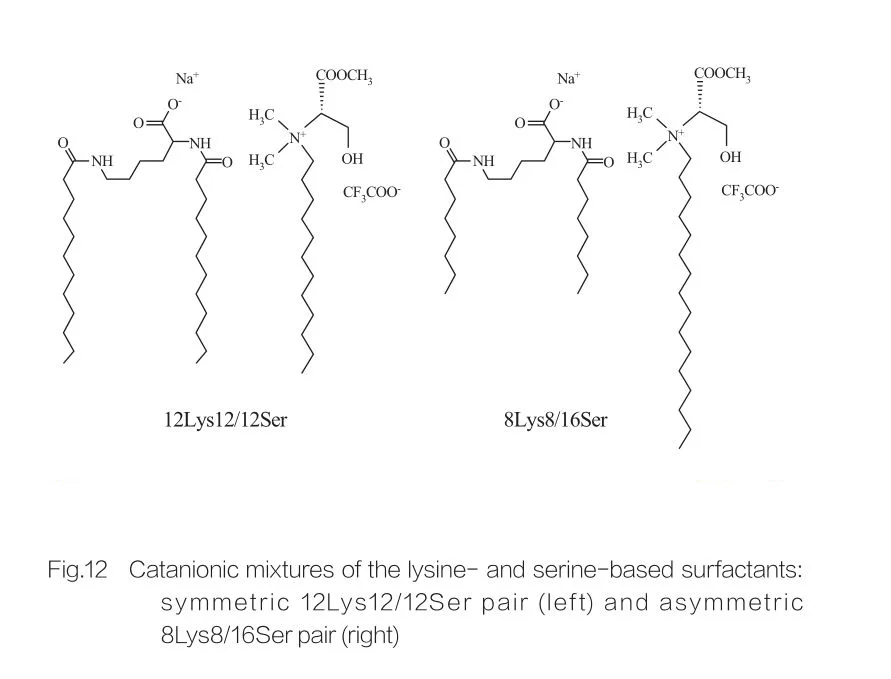

Phase Behavior

At high concentrations, surfactants exhibit isotropic discontinuous cubic phases. Surfactant molecules with large head groups easily form aggregates with small positive curvature. Marques et al. studied the phase behavior of 12Lys12/12Ser and 8Lys8/16Ser systems (see Figure 12), showing that the 12Lys12/12Ser system has a phase separation region between the micellar solution region and vesicle solution region, while the 8Lys8/16Ser system shows a continuous transition (elongated micelle phase region between small micelle phase and vesicle phase). Notably, in the vesicle region of the 12Lys12/12Ser system, vesicles always coexist with small micelles, while the vesicle region of the 8Lys8/16Ser system has only vesicles.

Emulsification Ability

Kouchi et al. examined the emulsification ability, interfacial tension, dispersion ability, and viscosity of N-[3-dodecyl-2-hydroxypropyl]-L-arginine, L-glutamate, and other AAS. Compared to synthetic surfactants (their traditional non-ionic and amphoteric counterparts), results showed that AAS have stronger emulsification ability than traditional surfactants.

Baczko et al. synthesized novel anionic amino acid surfactants and examined their suitability as chiral oriented NMR spectroscopy solvents. A series of sulfonate amphiphilic L-Phe or L-Ala derivatives with different hydrophobic tails (pentyl to tetradecyl) were synthesized by reacting amino acids with o-sulfobenzoic anhydride. Wu et al. synthesized sodium salts of N-fatty acyl AAS and examined their emulsification ability in oil-in-water emulsions, showing better performance with ethyl acetate as oil phase than n-hexane.

Hard Water Resistance

Hard water resistance can be understood as the surfactant’s resistance to ions such as calcium and magnesium in hard water, i.e., the ability to avoid precipitation into calcium soaps. Surfactants with strong hard water resistance are very useful for detergent formulations and personal care products. Hard water resistance can be evaluated by calculating changes in solubility and surface activity of surfactants in the presence of calcium ions.

Another method to evaluate hard water resistance is to calculate the percentage or grams of surfactant needed to disperse calcium soaps formed by 100 g sodium oleate in water. In areas with high hard water, high concentrations of calcium, magnesium ions, and minerals can pose difficulties for some practical applications. Sodium ions are usually used as counterions for synthesized anionic surfactants. Since divalent calcium ions bind to two surfactant molecules, surfactants more easily precipitate from solution, reducing detergency.

Studies on the hard water resistance of AAS show that acid resistance and hard water resistance are strongly influenced by an additional carboxyl group, and further increase with the length of the spacer between the two carboxyl groups. The order of acid resistance and hard water resistance is C12 glycinate < C12 aspartate < C12 glutamate. Comparing dicarboxylic amide bonds and dicarboxylic amino surfactants, the latter have a wider pH range, with surface activity increasing with moderate acid addition. Dicarboxylic N-alkyl amino acids have chelation effects in the presence of calcium ions, with C12 aspartate forming white gels. C12 glutamate exhibits high surface activity at high Ca2+ concentrations, promising for seawater desalination.

Dispersibility

Dispersibility refers to the ability of surfactants to prevent aggregation and sedimentation of surfactants in solution. Dispersibility is an important property of surfactants, making them suitable for detergents, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals. Dispersing agents must contain ester bonds, ether bonds, amide bonds, or amino groups between the hydrophobic group and terminal hydrophilic group (or in the linear hydrophobic group).

Typically, anionic surfactants such as alkanolamide sulfates and amphoteric surfactants such as amidopropyl betaines are particularly effective as calcium soap dispersants.

Many studies have measured the dispersibility of AAS, where N-lauroyl lysine was found to have poor compatibility with water, making it difficult for cosmetic formulations. In this series, N-acyl substituted basic amino acids have superior dispersibility and are used in the cosmetics industry to improve formulations.

Toxicity

Traditional surfactants, especially cationic surfactants, are highly toxic to aquatic organisms. Their acute toxicity is due to adsorption-ion interaction phenomena at the cell-water interface. Reducing the CMC of surfactants usually leads to stronger interfacial adsorption, often increasing acute toxicity. Increasing the length of the hydrophobic chain of surfactants also increases acute toxicity. Most AAS are low-toxic or non-toxic to humans and the environment (especially marine life), suitable as food ingredients, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics. Many researchers have proven that amino acid surfactants are mild and non-irritating to the skin. Arginine-based surfactants are known to be less toxic than their traditional counterparts.

Brito et al. studied the physicochemical and toxicological properties of amino acid-based amphiphiles and their spontaneously formed cationic vesicles derived from tyrosine (Tyr), hydroxyproline (Hyp), serine (Ser), and lysine (Lys), providing acute toxicity data to Daphnia magna (IC50). They synthesized cationic vesicles of dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide (DTAB)/Lys-derivatives and/or Ser-/Lys-derivatives mixtures, testing their ecotoxicity and hemolytic potential, showing that all AAS and their vesicle-containing mixtures are less toxic than traditional surfactant DTAB.

Rosa et al. studied the association of DNA with stable amino acid-based cationic vesicles. Unlike traditional cationic surfactants (usually toxic), the interactions of cationic amino acid surfactants appear non-toxic. This cationic AAS is based on arginine, which, when combined with certain anionic surfactants, spontaneously forms stable vesicles. Amino acid-based corrosion inhibitors are also reported as non-toxic. These surfactants are easy to synthesize with high purity (up to 99%), low cost, biodegradable, and fully soluble in aqueous media. Multiple studies show that sulfur-containing amino acid surfactants excel in corrosion inhibition.

Perinelli et al. in a recent study reported that rhamnolipids have satisfactory toxicological profiles compared to traditional surfactants. Rhamnolipids are known as permeability enhancers. They also reported the impact of rhamnolipids on epithelial permeability of macromolecular drugs.

Antimicrobial Activity

The antimicrobial activity of surfactants can be evaluated by minimum inhibitory concentration. The antimicrobial activity of arginine-based surfactants has been studied in detail. Gram-negative bacteria are found to have stronger resistance to arginine-based surfactants than Gram-positive bacteria. The antimicrobial activity of surfactants usually increases due to the presence of hydroxyl, cyclopropane, or unsaturated bonds in the acyl chain. Castillo et al. showed that the length of the acyl chain and positive charge determine the HLB value (hydrophilic-lipophilic balance) of the molecule, which indeed affects its membrane-disrupting ability. Nα-acyl arginine methyl esters are another important class of cationic surfactants with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, biodegradable, and low or no toxicity. Studies on interactions of Nα-acyl arginine methyl ester surfactants with 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine and 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine model membranes, and with living organisms with or without external barriers, show that this class of surfactants has good antimicrobial activity.

Biodegradability

Kamimura, Shida et al., and Kubo et al. extensively studied the biodegradability of amino acid surfactants, finding that N-acyl amino acids are easily biodegradable, decomposing into amino acids and fatty acids.

Compared to corresponding branched surfactants (such as bis-arginine compounds), surfactants with only one hydrophobic chain are relatively easier to biodegrade. Generally, the more hydrophobic the surfactant, the poorer its biodegradability. Akinari et al. synthesized fatty acid-based AAS and studied their physicochemical properties and biodegradability. Biodegradation experiments of these surfactants showed microbial degradation between 57%~73% over 14 days. Zhang et al. prepared supramolecular hydrogel mixtures of biosurfactants based on sodium deoxycholate and amino acids [such as glycine (Gly), alanine (Ala), lysine (Lys), and arginine (Arg)] using different buffer solutions, confirming their unique selectivity to multi-stimuli environments, easy biodegradability, and pH sensitivity, making them promising as carriers for dyes or drug delivery.

Hemolytic Activity

Nogueira et al. studied five lysine-based anionic AAS, differing in counterions, testing their ability to disrupt cell membranes at different pH ranges, concentrations, and incubation periods. For this purpose, they used a standard hemolysis assay as a model for endosomal membranes. Results confirmed that these surfactants have pH-sensitive hemolytic activity in the endosomal pH range and better kinetics.

It is well known that surfactants can interact with lipid bilayers of cell membranes. Erythrocytes are one of the most commonly used reference models for cell membranes to study the basic mechanisms of osmotic resistance caused by surfactants. By monitoring the effects of three arginine-based cationic AAS and five lysine-based anionic AAS on hypotonic hemolysis, Pérez et al. studied the mechanisms of surfactant-membrane interactions. Results showed that amino acid surfactants exhibit different anti-hemolytic behaviors. The physicochemical properties and structural characteristics of these compounds determine their protective role in preventing hypotonic hemolysis. There is a good correlation between the CMC of cationic surfactants and the concentration corresponding to maximum prevention of hypotonic hemolysis. In contrast, no correlation was observed for anionic surfactants. Lysine-based surfactants, differing only in counterions, determine whether they have anti-hemolytic efficacy or hemolytic activity.

Toxicological studies show that arginine-based monomeric and gemini surfactants disrupt red blood cell membranes depending on size and hydrophobicity.

Pinheiro and Faustino discussed interactions between erythrocytes and Nα,Nε-dioctanoyl lysine salts with different counterions (Li+, Na+, K+, Lys+, and Tris+). Interactions between surfactants and red blood cell membranes show opposite bidirectional patterns with concentration: preventing hypotonic hemolysis at low concentrations and causing hemolysis at high concentrations.

Rheological Properties

The rheological properties of surfactants are very important for determining and predicting their applications in different industries, including food, pharmaceuticals, oil extraction, personal care, and household care. Many studies have discussed the relationship between viscoelasticity and CMC of amino acid surfactants.

Industrial Applications

The special structure, non-toxicity, and biodegradability of AAS make them suitable for various industrial applications.

Applications in Agriculture

AAS can be used as insecticides, herbicides, and plant growth inhibitors in agricultural production. Betaine ester surfactants are a class of cationic surfactants that can be used as “temporary insecticides,” easily hydrolyzed into harmless components. A US patent reports a lawn insecticide synthesized from a mixture of refined oil extracted from Cupressaceae family plants and an amino acid-derived surfactant solution; where the amino acid-derived surfactant accounts for 20%~50% of the solution weight. The herbicidal effects of non-ionic AAS have also been reported.

Applications in Laundry

Currently, global demand for amino acid-based detergent formulations is increasing. AAS are known to have better cleaning ability, foaming ability, and fabric softening performance, making them suitable for household detergents, shampoos, body washes, etc. An amphoteric AAS derived from aspartic acid is reported as an efficient chelating detergent. Detergent components composed of N-alkyl-β-amino ethoxy acids are found to reduce skin irritation. Liquid detergent formulations composed of N-cocoyl-β-aminopropionates are reported as effective cleaners for oil stains on metal surfaces. An aminocarboxylic acid surfactant C14CHOHCH2NHCH2COONa is also proven to have better detergency and used for cleaning textiles, carpets, hair, glass, etc. 2-Hydroxy-3-aminopropionic acid-N,N-diacetic acid derivatives are known to have good complexing ability, thus imparting stability to bleaches.

Detergent formulations based on N-(N’-long-chain acyl-β-alanyl)-β-alanine are reported to have better detergency and stability, easy foam breaking, and good fabric softness. Keigo and Tatsuya reported in a patent the preparation of acyl amino acid-based detergent formulations. Kao formulated detergent formulations based on N-acyl-1-N-hydroxy-β-alanine and reported low skin irritation, high water resistance, and high detergency.

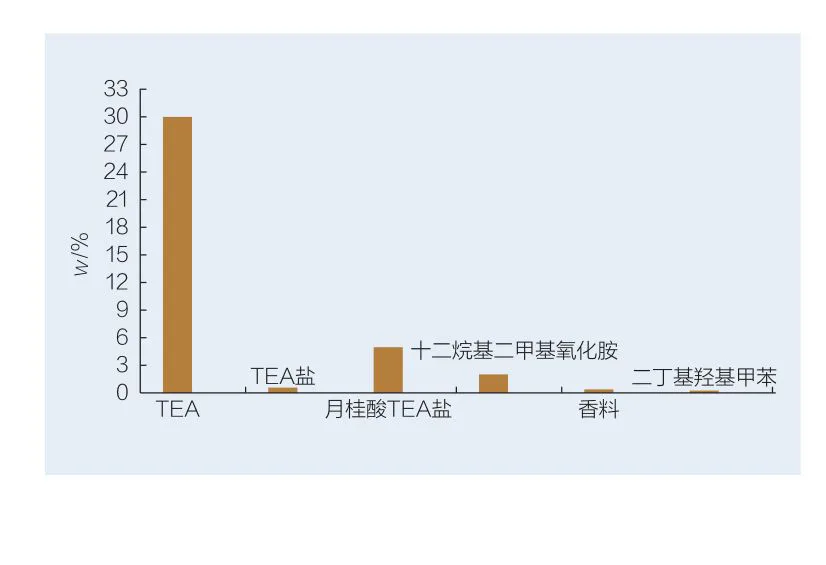

Japan’s Ajinomoto company uses low-toxic and degradable AAS based on L-glutamic acid, L-arginine, and L-lysine as main components in shampoos, detergents, and cosmetics (Figure 13). The ability of enzyme additives in detergent formulations to remove protein stains has also been reported. N-acyl AAS derived from glutamic acid, alanine, methylglycine, serine, and aspartic acid are reported as excellent liquid cleaners in aqueous solutions. These surfactants do not increase viscosity even at very low temperatures, can be easily transferred from storage containers of foaming devices, thus obtaining uniform foam.

Lubricants

Amphoteric AAS are commonly used as lubricants. They have low friction coefficients and excellent adhesion to hydrophilic surfaces, making them ideal lubricants. Many researchers have prepared and studied the lubricating characteristics of AAS, especially glutamic acid.

Applications in Pharmaceuticals

Drug Carriers and Functional Liposomes

In recent years, many researchers have reported the ability of synthesized acyl amino acids/peptides as drug carriers and for preparing functional liposomes with lipopeptide ligands. Vesicles of long fatty chain Nα-acyl amino acids also show solute encapsulation rates compared to traditional lecithin liposomes.

Gene Therapy and DNA Transfection

Gene therapy is an important technology in current life sciences, safely introducing selected genes into living cells. Gemini surfactants have potential as carriers for transporting bioactive molecules. Using standard peptide chemistry, cationic gemini surfactants based on lysine and 2,4-diaminobutyric acid can be easily synthesized.

McGregor et al. prepared a new class of gemini amino acid surfactants as carriers for delivering genes into cells. Preliminary results show that combining these gemini amino acid surfactants with dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE) can synthesize liposomes of different sizes and lipid compositions. Studies show that suspensions formed by DOPE/surfactant mixtures in water yield mixtures of lipid vesicles with more complex structures and particle diameters of about 500 nm. Different molar ratios of DOPE/surfactant mixtures (50/50, 60/40, and 70/30) have comparable effects on luciferase expression in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. Colloid size and molecular composition of gemini surfactants are important for optimal gene expression in in vivo models.

Pena et al. evaluated the DNA transfection rates of low-molecular-weight cysteine-based AAS and their corresponding gemini. These surfactants showed no cytotoxicity and, compared to similar products on the market, they more effectively transfect CHO-K1 (Chinese hamster ovary) cells.

Antiviral Agents

Due to significant antiviral activity, lipoamino acids have attracted researchers’ attention. Certain acyl amino acid derivatives are also reported to inhibit influenza neuraminidase. Some Nα-palmitoylated amino acids/peptides, when incorporated into model membranes, affect the transition temperature (from bilayer to hexagonal aggregation).

Cationic surfactant derivatives of AAS obtained by condensation of fatty acids (such as lauric acid) with esterified binary amino acids (such as arginine) can be developed to resist microorganisms, and these cationic surfactants are also found effective against viral infections. Additionally, adding N-α-lauroyl-L-arginine ethyl ester to cultures of Herpes virus type 1, Vaccinia virus, and bovine parainfluenza virus type 3 leads to almost complete elimination of viral organisms in the cultures, observable from 5~60 min.

Applications in the Cosmetics Industry

AAS are used in formulations for various personal care products. Potassium N-cocoyl glycinate is found mild on skin and used in facial cleansing to remove dirt and makeup. N-acyl-L-glutamic acid has two carboxyl groups, thus better water solubility. Among these AAS, C12 fatty acid-based AAS are widely used in facial cleansing to remove dirt and makeup. AAS with C18 chains can be used as emulsifiers in skincare products. N-lauroyl alanine salts are known to produce creamy foam non-irritating to skin, thus for formulating baby care products. N-lauroyl-based AAS used in toothpastes have good detergency similar to soaps and strong enzyme-inhibiting efficacy.

In the past few decades, the selection of surfactants for cosmetics, personal care products, and pharmaceuticals has emphasized low toxicity, mildness, gentle touch, and safety. Consumers of these products have a deep awareness of potential irritancy, toxicity, and environmental factors.

Today, because AAS have many advantages in cosmetics and personal care products compared to traditional counterparts, they are used to formulate many shampoos, hair dyes, and bath soaps. Protein-based surfactants have ideal characteristics essential for personal care products. Some AAS have film-forming ability, while others have good foaming ability.

Amino acids are important natural moisturizing factors present in the stratum corneum. When epidermal cells die, they become part of the stratum corneum, and intracellular proteins gradually degrade into amino acids. These amino acids are then further transported into the stratum corneum, absorbing fats or fat-like substances into the epidermal stratum corneum, thereby improving skin surface elasticity. About 50% of natural moisturizing factors in the skin are composed of amino acids and pyrrolidone.

Collagen is a common cosmetic ingredient containing amino acids that can keep skin soft. Skin problems like roughness and dullness are largely due to lack of amino acids. A study showed that mixing an amino acid with ointment can relieve skin burns, and the affected area recovers to normal without becoming keloids.

Amino acids are also found very useful for caring for damaged cuticles. Dry and dull hair may indicate a decrease in amino acid concentration in severely damaged cuticles. Amino acids have the ability to penetrate the cuticle into the hair shaft and absorb moisture from the skin. This ability of amino acid surfactants makes them very useful in shampoos, hair dyes, softeners, conditioners, and the presence of amino acids makes hair strong.

Applications in Microbial Enhanced Oil Recovery

AAS are also useful in microbial enhanced oil recovery. A strain, Brevibacterium aureum MSA13, synthesizes an AAS with potential for microbial enhanced oil recovery. This surfactant has stearic acid as the hydrophobic part, and the hydrophilic group consists of a tetrapeptide (short sequence of 4 amino acids: pro-leu-gly-gly). Another example involves microbial enhanced oil recovery in marine environments, using a surfactant produced by actinobacterium MSA13.

Applications in Nanomaterials

Polymerizable surfactants based on amino acids are also useful in synthesizing chiral nanoparticles. Preiss et al. reported the synthesis of chiral surfactants based on amino acids with polymerizable segments, then developed for preparing chiral surface-functionalized nanoparticles. They also tested their potential as nucleating agents for enantioselective crystallization of racemic amino acid mixtures (using racemic asparagine as model system). Comparing particles synthesized from chiral surfactants with different hydrophobic tails, results showed that only chiral nanoparticles composed of polymerizable surfactants can effectively act as nucleating agents in enantioselective crystallization processes.

Other Applications

AAS can also be used to form PEDOT [poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)] films. PEDOT films are prepared by direct anodic oxidation of EDOT (3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) in aqueous solutions containing sodium N-lauroyl sarcosinate (an environmentally friendly AAS). Besides the above applications, AAS are also used to optimize dry cleaning processes using carbon dioxide as chiral solvent.

Van Roosmalen et al. optimized dry cleaning processes using carbon dioxide and AAS, studying the effects of various parameters on cleaning. Parameters studied include cleaning time, temperature, and mechanical power. The effects of CO2, isopropanol, water, and surfactant usage were also studied.

Self-assembly of AAS leads to formation of micelles with chiral surfaces. This property of AAS micelles (supramolecular chirality) makes them suitable for asymmetric organic synthesis. Chiral micelles can also impart chirality to mesoporous materials prepared by surfactant template methods, making their mesopores chiral. Dicarboxylic-based AAS can also act as surface-active chelating agents. Observations show that interactions of dicarboxylic AAS with divalent ions (like calcium) depend on the distance between the two carboxyl groups.

For example, N-acyl glutamate has two carboxyl groups separated by two secondary carbons and one tertiary carbon gene, unable to form intramolecular chelates with calcium ions, and does not precipitate with high calcium ion concentrations in water. The binding properties of chelating surfactants can also be used for mineral flotation. Calcium-containing minerals, such as calcite and apatite, can be separated by flotation reagents with appropriate distances between carboxyl groups. N-alkyl AAS are true amphoteric surfactants that provide very low surface tension at CMC due to formation of self-assemblies composed of alternating anionic and cationic types. This is a representative example of micellization-driven protonation of surfactants.

AAS can also be used to design switchable surfactants. The most famous example in this class of AAS is cysteine derivatives, which can easily convert to cystine derivatives through reversible processes. For example, long-chain N-acyl cystine is a highly surface-active gemini surfactant that can be converted to cysteine derivatives. Dithiothreitol has poor surface activity and can also be restored to gemini surfactant through an oxidation reaction. The transition from one state to another can also be achieved by electrochemical methods.

Current Challenges Facing AAS

Whether large-scale production of AAS is economically feasible is a primary consideration. The biotechnological processes involved in production are not easy to make cost-effective, especially for fields requiring large amounts of surfactants, such as petroleum and environmental applications. Purification of substances is another issue that must be addressed, essential for pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and food applications. Besides these drawbacks, denaturation and decomposition of AAS cannot be ignored, and their activity is largely affected by salt solutions.

Many researchers have proposed methods to solve these problems. By using waste substrates (after eliminating their pollution effects), the total production cost can be reduced. Developing effective bioprocesses and successfully optimizing them is also essential, including optimizing culture conditions, low-cost recovery processes, to maximize production and recovery.

Summary and Outlook

Since the first study on simple AAS synthesis in 1909, AAS research has now expanded to the production of cationic, anionic, non-ionic, and amphoteric molecules, their detailed characterization, and evaluation of physicochemical properties. AAS have been proven to have wide applications in different industrial fields, and due to the diversity of properties brought by their potential structural diversity, their application scope will further expand in the future. Examples show that using the chirality of AAS makes the surfaces of mesoporous materials prepared by micelle template methods chiral. In suitable fields, when selecting surfactants, the easy degradability and non-toxicity of AAS can make them superior to traditional synthetic surfactants.

The main challenges facing AAS are high production costs and difficulties in separating high-purity products. By selecting suitable renewable substrates for substitution and designing economic and scalable processes, many researchers are working to address these issues. Given the diversity of their structures and physicochemical properties, in the near future, AAS are likely to be widely accepted and commercialized in various industrial fields.

For more on amino acid surfactants and our range of bio-based surfactants, visit BookChem offerings at Amino Acid Surfactant Products. As experts in sustainable chemistry, Book Chem continues to innovate in amino acid surfactants for eco-friendly solutions.

Summary of Surfactant Knowledge Points

Surfactant

A Series for Easy Understanding

Green surfactants

Synthesis, Properties, and Industrial Applications of Amino Acid Surfactants